Dit artikel is geschreven in het Engels en is nog niet vertaald naar het Nederlands.

The Neuroscience of Visual Persuasion in Arbitration

At the Dutch Arbitration Day 2025, we had the opportunity to present alongside Michael Arch from FTI Consulting on Effective Visual Arguments: Dos and Don'ts. Our session explored how cognitive science principles can improve arbitration advocacy—a practical challenge we all face.

Co-founder

Maurits combines legal expertise with technical implementation and design thinking. With a background in litigation, he specializes in creating strategic frameworks and technical solutions for complex legal challenges. His work focuses on making legal information more effective through thoughtful structure and technology.

Your case is complex. The stakes are high. You know visuals could help - but where do you start? Here's your practical guide to building a visual strategy that works.

Real-world examples of how visual communication transforms complex litigation, featuring two high-stakes cases and their outcomes

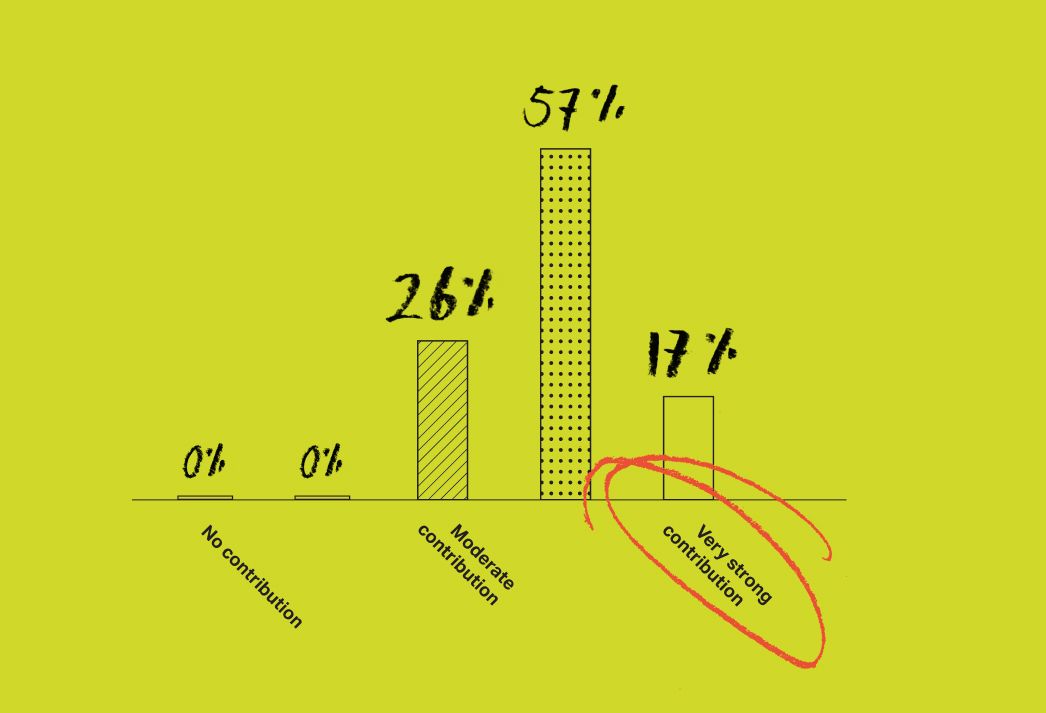

A data-driven look at how visual communication affects litigation outcomes and client satisfaction, based on research across 200+ cases

Your case is complex. The stakes are high. You know visuals could help - but where do you start? Here's your practical guide to building a visual strategy that works.